To this day, only one NCAA Division I football program has ever received the death penalty.

A few universities have come close, but none have faced the harshest penalty — which bans a team from competing for at least a year and heavily reduces scholarships — since Southern Methodist University's football team in 1987.

The NCAA nearly brought that same hammer down on Alabama in 2002 for a pay-for-play recruiting scandal and Penn State football in 2012 for a child sex abuse scandal.

Despite the severity of those cases, particularly in the Penn State case, the NCAA has been reluctant to impose the death penalty, opting instead to reduce scholarships, vacate wins and hand out postseason bans and hefty fines.

As the former University of Florida President John Lombardi perfectly put it, the death penalty is like a nuclear bomb: "The results were so catastrophic that now we'll do anything to avoid dropping another one."

That's why the death penalty itself received, well, the ultimate death penalty.

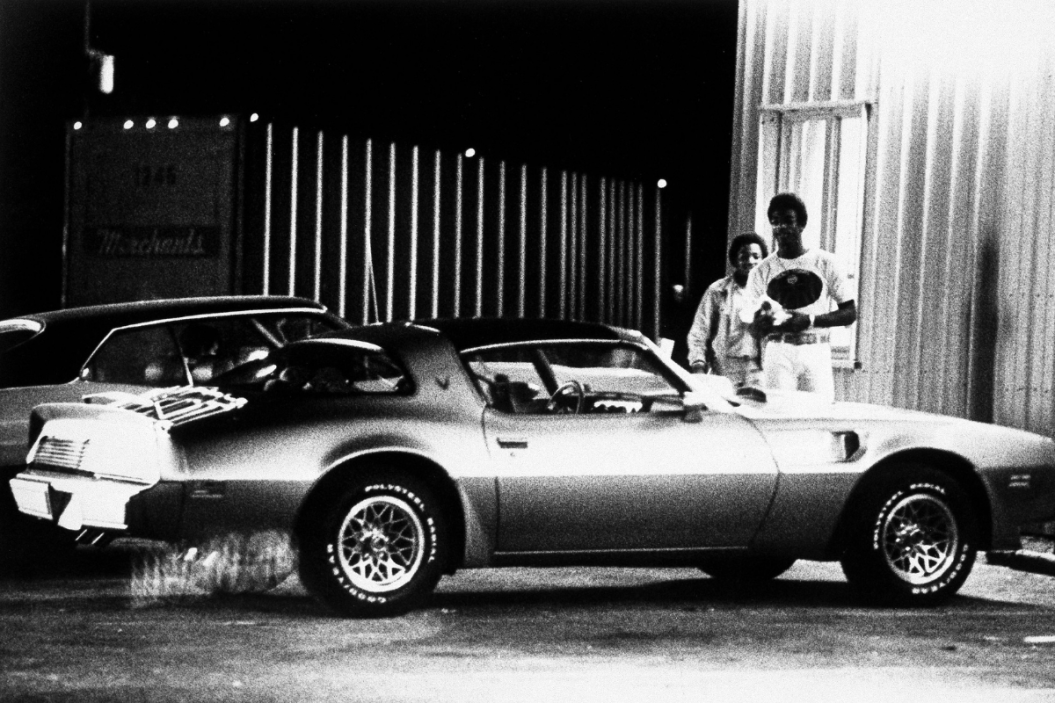

That precedent can maybe be traced back to one single car: Eric Dickerson's "Trans A&M."

Before the running back was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1999, before he set the NFL single-season rushing record (previously held by O.J. Simpson) with the Los Angeles Rams in 1984 and before he compiled a legendary career at SMU that established the Mustangs as one of the elite programs in the country, he raised eyebrows when he began driving a gold Pontiac Trans-Am while still a blue-chip recruit at Sealy High School in Sealy, Texas.

Eric Dickerson's "Trans A&M"

RELATED: SMU's Death Penalty Changed College Football Forever

Legend has it that Eric Dickerson began carting himself around in the gold Trans-Am around the same time he committed to play in College Station for the Texas A&M Aggies in 1979, leaving many to question if Texas A&M recruiters had given him the car.

When he suddenly chose SMU over schools such as TAMU, Oklahoma and Texas, the muscle car disappeared. One myth claims a vengeful Aggie destroyed it in retaliation to his decision.

Dickerson was one of the biggest names in that year's recruiting class. Texans that were football fans at the time will tell you virtually every school in the Southwestern United States wanted him. One recruiter from the University of Texas even cried when he didn't choose the Longhorns.

Dickerson has denied that the car was a gift from any school. He claims in a Houston Chronicle article his grandmother gave it to him and that he sold it to a friend between his junior and senior years in high school, though it was later stolen.

But in ESPN's 30 for 30 "Pony Excess," former SMU assistant Steve Endicott claimed TAMU made the down payment on the car and SMU officials helped him pay for it while at SMU.

In that same ESPN special, Dickerson admitted that Texas A&M recruiters showed he and his grandmother a briefcase containing $50,000.

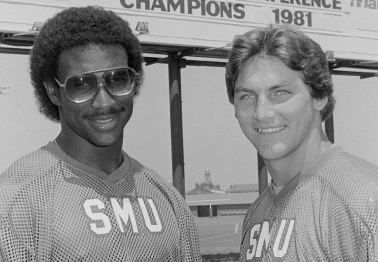

Dickerson, of course, went to SMU and formed the Pony Express backfield alongside another blue-chip running back in Craig James.

The duo helped the Mustangs win Southwest Conference (SWC) titles in 1981 and 1982 and made them a legitimate national championship contender.

Dickerson was an All-American and finished third in the 1982 Heisman Trophy voting behind John Elway and Herschel Walker. He rushed for more than 3,000 yards and 36 touchdowns over his final two years there. He then played 11 seasons in the NFL with the Rams, Indianapolis Colts, Los Angeles Raiders and Atlanta Falcons.

SMU's Death Penalty & Aftermath

Dickerson's formidable recruiting class was one of many stellar ones SMU coach Ron Meyer put together when he took over in 1976. SMU football was already a storied program: They'd produced four Hall-of-Famers and one national championship in 1935.

But the Mustangs hadn't consistently won since that until winning 10 games in five-straight seasons from 1980-84. Meyer, however, took off for the NFL in 1982 years before the NCAA imposed any penalties.

Reporters at the time — including then-Dallas Morning News reporter Skip Bayless — even asked Meyer how in the world he convinced these high school football players to choose SMU over the giants such as Texas, Texas A&M and Oklahoma.

"You know, Skip, it's just the damnedest thing with high school kids. You never know what they're going to decide."

— Former SMU head coach Ron Meyer.

We don't know which schools still pay players, but it most certainly still happens if you believe reports. The thing is, it's incredibly hard to track. We may never know exactly what Dickerson was offered by SMU or why he had a sudden change of heart, but we know he wasn't the last to receive gifts or money. Considering today's age where NIL deals are all the rage, Dickerson probably wishes he played now.

SMU, meanwhile, still hasn't recovered from the penalties. The Mustangs have had decent seasons over the last decade. They've been to four bowl games, including in 2012, 2017, 2019 and 2021. They requested to join the Big 12 but were denied.

After leaving SMU, Dickerson made NFL history as a rusher. From the day he was taken second in the 1983 NFL Draft until the day he set a National Football League record that is unlikely to be broken with 2,105 rushing yards in a single campaign, he earned a Hall of Fame career.

He also left his alma mater behind him as it crumbled.

Dickerson's "Trans A&M" wasn't the sole reason SMU received the death penalty, but it represented an era in which SMU and (according to Dickerson) other major schools were paying players and committing major NCAA recruiting violations.

For that, it changed college football forever.

This post was originally published on June 12, 2019.