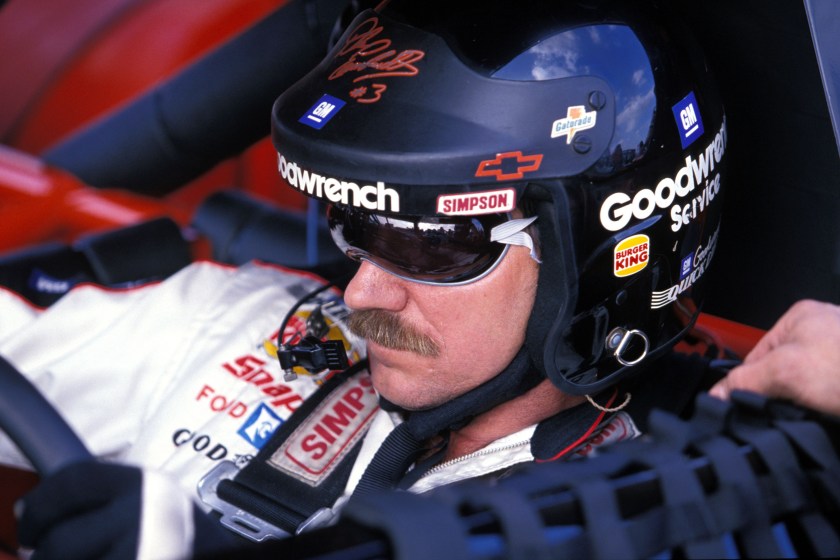

When Dale Earnhardt arrived at Sonoma Raceway in May 1995, the driver of the iconic black No. 3 car had already accomplished more in his legendary career than most have or ever will.

Videos by FanBuzz

Those accomplishments included a record-tying seven championships in NASCAR's premier series and more than 60 premier series wins. Notably missing from Earnhardt's Hall-of-Fame resume, however, was a win on a road course. And that went for any road course — not just Sonoma, the 2.52-mile winding road circuit in Northern California's beautiful Wine Country.

To break it down, Earnhardt's record on record courses coming into the 1995 Cup Series weekend at Sonoma went like this:

- 0-for-20 at Riverside International Raceway (which hosted its last Cup event in 1988)

- 0-for-9 at Watkins Glen International

- 0-for-6 at Sonoma

I'm no math whiz, but it appears that those numbers add up to Earnhardt being an ugly 0-for-35 at road courses up until that point.

Not that the driver nicknamed "The Intimidator" was bad on road courses. In all reality, he was actually pretty decent on them and had enjoyed some strong outings on all three road circuits he'd competed on. His problem was simply that he hadn't been able to get over the proverbial hump and get to Victory Lane, which he ultimately did only once at a road course in his illustrious career.

For most of the 1995 Save Mart Supermarkets 300 at Sonoma, Earnhardt ran true to his typical road course form. Translation: he was in the hunt, but a win seemed likely. That was primarily because Mark Martin — the Cup Series' resident road course ace — paced the field for a whopping 66 of 74 laps in his No. 6, Valvoline-sponsored Roush Racing Ford after starting from the third position.

Martin appeared to have the race well in hand as the event entered its final laps, despite Earnhardt's Richard Childress Racing Chevrolet lingering only a few car lengths behind in his rearview mirror.

But just when it appeared that Martin would likely be able to hold Earnhardt at bay and keep The Intimidator winless on road courses, Earnhardt's black No. 3 blew past Martin in turns 5 and 6 — the portion of the track known as the Carousel — when Martin's car momentarily slid in oil that another car had laid down on the track.

The slip-up was just enough for Earnhardt to take advantage, seizing the top spot for the only two laps he would lead all race. He beat Martin to the checkered flag by just over three-tenths of a second.

After pulling into Victory Lane, the jubilant driver of the No. 3 car climbed out of the vehicle with steering wheel in hand — something he never did before or after that day — and, after embracing wife Teresa, left no doubt about how much this breakthrough triumph meant to him.

"Well, I've won a road course," a beaming Earnhardt said, looking like the weight of the world had been lifted from his shoulders. "Maybe I can break the ice and win Daytona next year."

Earnhardt was referring to his 0-for-17 record in NASCAR's biggest race, the Daytona 500, which he finally captured in 1998 in his 20th try.

But that Sunday at Sonoma was all about putting to bed another drought — one that had lasted his entire career and one that he'd clearly spent some time pondering.

"I don't know why we hadn't won a road course until now," Earnhardt told his good friend, Dr. Jerry Punch of ESPN, during his televised Victory Lane interview. "We've been close."

Earnhardt then described, from his vantage point, the dramatic turn of events that took place in the final two laps.

"I sat there behind Mark and ran a real good, smooth race, and everybody pressuring me from behind just wasn't a contender," he said. "I could just take care of my tires and just move on, but Mark had really beat me off these long corners.

"Well, in the last couple of laps, somebody threw some grease out, and that was a little deterrent, and he slipped and slid, and he slipped out on the Carousel, and I got under him, and that's all it took."

In August of the next year, Earnhardt enjoyed another career-defining moment on a road course — this time at Watkins Glen, the 2.45-mile Upstate New York circuit where he was competing all while nursing a broken collarbone and sternum suffered in a violent accident two weekends earlier at Talladega Superspeedway in Alabama.

After being forced to give way to a relief driver on Lap 6 of the Brickyard 400 just six days after his crash, Earnhardt was hell-bent on qualifying and then going the full 90-lap distance at The Glen. Despite being in tremendous pain, he did just that — finishing sixth after winning the pole in a feat that even today is widely considered one of the most heroic driving displays in NASCAR history.

But that was Dale Earnhardt. He was a force of nature and force to be reckoned with. Even on road courses.