Southern Methodist University wasn't always a middling college football program. Back in the early 1980s, the Mustangs were enjoying a massive string of success. In order to achieve that success, however, SMU was forced to bend many rules, particularly in recruitment.

When the NCAA discovered the college athletics program's wrongdoing, it dropped the hammer on the Dallas-based program, severely crippling SMU to the point where the incident is now referred to as the "death penalty."

Welcome to one of the most damaging and shocking moments in college sports history.

SMU Football Program Receives the "Death Penalty"

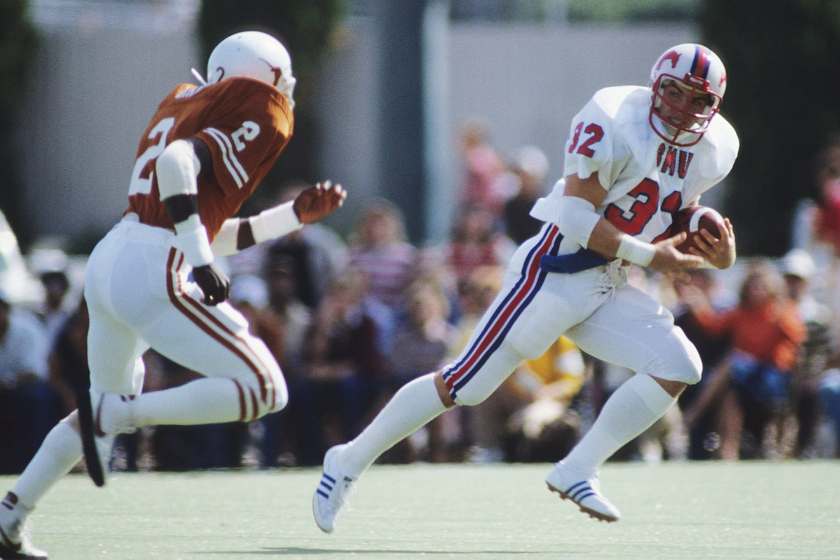

Photo by Ronald C. Modra/Getty Images

RELATED: The Legend of Eric Dickerson's "Trans A&M" & How it Shook College Football

Offering high school football players benefits in order to lure them to your team is an illegal act under NCAA guidelines, even in the age of NIL. The Southern Methodist University football program didn't care. They were able to land some top high school prospects whom otherwise wouldn't have given the program a second look.

SMU was never a sought-after destination for student athletes like Notre Dame, TCU, Miami, Oklahoma, USC in Los Angeles, or Alabama today, but they managed to lure some of the country's best players to their ranks.

Head coach Ron Meyer, who took over in 1976, led the charge in terms of SMU's illegal recruiting practices.

While it's not known precisely how many players were offered illegal benefits by the program, the most notable name to join the program under shady circumstances was Hall of Fame running back Eric Dickerson, who spurned Texas A&M at the last minute to join Meyer at SMU.

It's become a running joke in football circles that Dickerson had taken a pay cut when joining the NFL, signifying just how great the benefits he received from Meyer were.

Dickerson helped the SMU football achieve new heights, becoming a dominant force in the Southwest Conference. He rushed for 47 touchdowns across four seasons, including 38 during his final two years with the program.

During those two campaigns, the Mustangs recorded a 21-1-1 record, including an undefeated season in 1982 under head coach Bobby Collins, winning the SWC and the Cotton Bowl against Pittsburgh. T

hey were ranked as highly as No. 2 in the Associated Press' Top 25, and were even contending for the National Championship, though a tie against Arkansas put an end to that dream.

The SMU backfield of Dickerson and Craig James was dubbed the "Pony Express" and ESPN released a 30-for-30 documentary titled Pony Excess (Pony Exce$$) about the shady recruitment of Dickerson to SMU.

SMU was never able to replicate its success after Dickerson turned pro. The program instead continued its payments to players, however at a significant cost. Sean Stopperich, a high school offensive lineman who was paid $5,000 to join the Mustangs football program, had blown his knee out in high school and spent just one year with the program.

Upon departing from SMU, he served as a key witness for the NCAA's investigation into the program. It was discovered by the NCAA that a slush fund from the athletic department and boosters had paid out over $61,000 to 13 players between 1985-86.

The sanctions issued were harsh. SMU was banned from bowl games for two seasons and the program was stripped of 45 scholarships. Such extreme penalties were never before seen in Division I college football, yet somehow, the program didn't cease it's illegal operations.

Despite vowing to stop paying its players, Bill Clements, chairman of SMU's board of governors, decided to continue paying players it had promised money to up until their graduation, further violating NCAA rules.

David Stanley, a former SMU linebacker, was one of the players receiving benefits, and after he was kicked off the team he didn't hesitate to come forward and expose the continued malpractices occurring at SMU.

Stanley's comments, paired with a disastrous interview from Coach Collins, athletic director Bob Hitch, and recruiting coordinator Henry Lee Parker effectively sealed the program's fate. WFAA's Dale Hansen and the Dallas Morning News, effectively got Parker to admit to the program's recruiting violations during the interview, resulting in the next wave of sanctions upon the program.

After deliberation, the NCAA decided to hand down the death penalty on the Texas-based program, due to it being a repeat violator.

The SMU football team had its season cancelled in 1987, and removed all four of its home games in 1988. The team's postseason/bowl game ban was extended until 1989, they were stripped of a total of 55 scholarship positions, nine boosters were banned from having any contact with the team, and the team was not allowed to hire more than five assistant coaches.

Had SMU not cooperated in the investigation, there's a real chance the program's football team would have been shut down for good.

NCAA Director of Enforcement David Berst handed down the punishments to the program, and then promptly fainted in front of the assembled media members. SMU's fate was sealed.

Aftermath for the Mustangs

Photo by Robert Seale via Getty Images

RELATED: Ohio State's Tattoo Scandal Ruined Jim Tressel's Coaching Career

Since the hammer was dropped on SMU, the first time college football had ever witnessed such severe punishments, the Mustangs recorded just one winning season from 1989-2008, and only a handful since then.

When Forrest Gregg took over as head coach in 1989, the team was severely depleted, as the football scandal had crippled the program's ability to recruit players. It also didn't help that the Mustangs played in the same conference as Heisman winner Andre Ware of Houston that year.

SMU has bounced around conferences since the infractions committee stuck the dagger in the program. The Southwestern Conference, where SMU had played the likes of Baylor, Rice and Houston, fell apart in 1996. The Mustangs were in the WAC and Conference USA before settling down in the American Athletic Conference. They were excluded from consideration when the Big 12 conference formed in 1994, effectively losing out on becoming a Power 5 program.

The SMU scandal set the precedent for future violations of NCAA rules, though it didn't dissuade teams from trying to get an edge. Currently, a few teams are at risk of facing similar sanctions, most notably Baylor.

The risk in violating recruitment practices has been made clear, and SMU bore the brunt of the penalties in order to set the tone for other programs who may have been thinking about illegally recruiting talent.

This article was originally published on January 1, 2021, and has been updated since.