Tim Tebow is a lot of things. He's the greatest college quarterback of all time. He's a baseball-playing, sports-commentating, New York Times best-selling author and motivational speaker.

Videos by FanBuzz

Despite all the good, charitable and humanitarian work the former Florida Gators and Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback has done since graduating, he is still painfully ignorant to what has helped him in every step of life: his privilege.

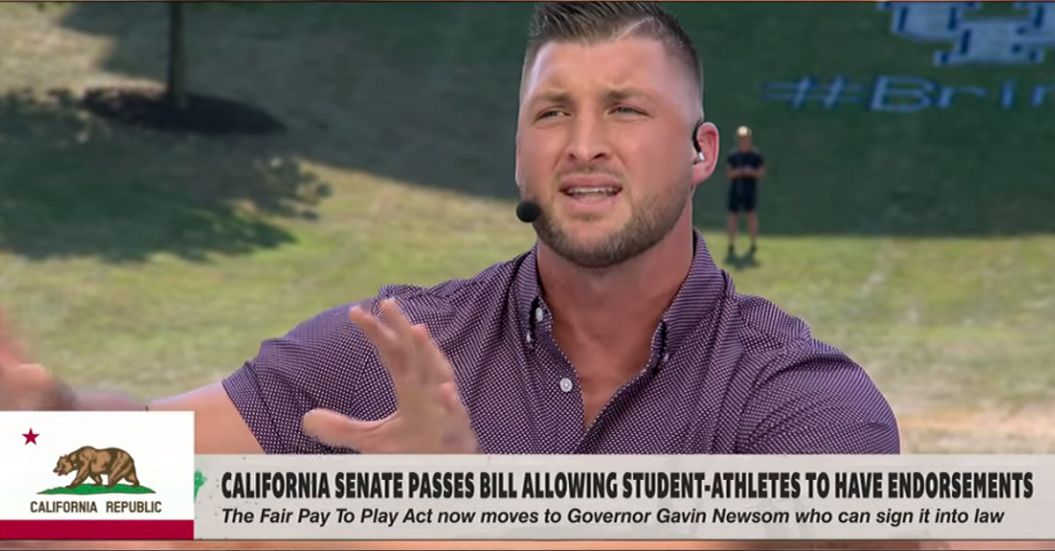

The ESPN and SEC Network employee joined Stephen A. Smith and Max Kellerman on ESPN First Take to share his opinion regarding college athletes being paid. The California senate just recently passed the Fair Pay to Play Act, which would give NCAA athletes the ability to profit off their name, image and likeness.

The bill, which still has to clear many hurdles before becoming law as early as 2023, has been supported by professional athletes and sports media members like NBA and Los Angeles Lakers star LeBron James. The reason for that is simple: College athletes shouldn't have to starve or scrape by when they are making millions of dollars for their universities.

Tebow vehemently disagrees with that sentiment:

Tim Tebow on First Take

.@TimTebow passionately expresses his thoughts on the California Senate passing a bill allowing student-athletes to have endorsements. pic.twitter.com/W5uBW7ePNm

— First Take (@FirstTake) September 13, 2019

"I feel like I have a little credibility and knowledge about this, because when I was at the University of Florida I think my jersey was one of the top-selling jerseys around the world. It was like Kobe, LeBron and then I was right behind them. And I didn't make a dollar from it, but nor did I want to because I knew going into college what it was all about. I know going to Florida, my dream school, where I wanted to go, the passion for it, and if I could support my team, support my college, support my university, that's what it's all about.

"But now we're changing it from "us", from "we", from "my university", from being an alumni where I care which makes college football and college sports special, to then, "OK, it's not about us. It's not about we. It's just about me." And yes I know we live in a selfish culture where it's all about us but we're just adding and piling on to that where it changes what's special about college football. We've turned it to the NFL, where who has the most money, that's where you go. That's why people are more passionate about college sports than they are NFL. That's why the stadiums are bigger in college than they are in NFL. Because it's about your team. It's about your university. It's about where my family wanted to go. It's about where my grandfather had a dream of seeing Florida win an SEC Championship. And you're taking that away so that young kids can earn a dollar. And that's just not where I feel like college football needs to go. There's that opportunity in the NFL, but not in college football."

Tebow says he didn't want to make money off his jersey sales. That's because Tebow is a privileged white male who didn't need money while attending college. Not everyone is so lucky.

A sheltered home-schooled boy who grew up on his family's 40-acre farm in Jacksonville, Florida, Tebow came from money. His parents — Pamela and Robert — met at the University of Florida and moved to the Philippines, where they built a ministry as wealthy Baptist missionaries. They moved Tebow and their four other children to the Sunshine State when the future NFL quarterback was just three.

Compared to the upbringings of many black college football players, Tebow's childhood embodies the term privilege. As a young boy, he had a pool behind his house. A basketball hoop stood tall in the driveway. His dad even built him a batting cage, according to a Bleacher Report article.

Of course, Tebow was a tremendously gifted athlete playing football and baseball at Nease High School, but he also had every opportunity to become a superstar athlete. He won a huge playoff game against the Pittsburgh Steelers but fizzled out of the NFL with the Denver Broncos and New York Jets. He was handed a TV analyst job afterward. He even signed a professional baseball contract with the New York Mets of the MLB despite not playing since high school.

That privilege and fame made Tebow's Florida jersey one of the highest-selling ever, which is still sold online and in stores to this day.

Tebow claims the Fair Pay to Play Act is about selfishness. He believes that players are only thinking of themselves by wanting compensation for their hard work and dedication to their craft.

Wrong.

Many college athletes want to help their families or whomever helped them get that scholarship. Many come from broken families, poverty and unstable homes. The odds are stacked high against them.

Knowshon Moreno, a former NFL running back who played against Tebow at Georgia, was born to an unmarried couple in the Bronx, New York, and bounced from homeless shelter to homeless shelter with his father growing up.

Dez Bryant's mother was 14 when she had him and was arrested when she was 22 for dealing crack cocaine to provide for her family. Bryant lived in eight different homes during his high school career in Texas but still went on to star at Oklahoma State.

You trippin Tim Tebow https://t.co/zYWyI51IEo pic.twitter.com/OFRc4DZINI

— Dez Bryant (@DezBryant) September 13, 2019

Tim Tebow this is a learning session pic.twitter.com/Rbrh9dbcvb

— Dez Bryant (@DezBryant) September 13, 2019

RELATED: UL Coach Asks Unpaid Players to Donate $50 in New, Tone-Deaf Rule

Shabazz Napier, who helped win a national championship for UConn's men's basketball team, said some nights he went to bed starving. Meanwhile, the NCAA rakes in some $900 million from the NCAA Tournament alone.

Is it really selfish for an athlete to recognize they make a school millions of dollars and want some of that? Take for example how the NCPA, a nonprofit organization founded by former UCLA athletes, estimates Texas football players are valued at $513,922 and Duke basketball players at $1,025,656 each.

Maybe you agree with Tebow. A free education is more than enough compensation. We should preserve the NCAA's amateurism for fear of turning it into the NFL, right?

Wrong again.

NCAA athletes aren't receiving the same educational experience as non-athletes. Often times they are forced to pick from a list of worthless majors that allow them time to travel, practice, lift weights and study film.

Then there's the fact that student-athletes aren't even receiving a cost-free diploma a good amount of the time. A 2010 study revealed that the average football and basketball player actually ends up paying close to $3,000 a year in out-of-pocket costs.

Plus, graduation rates for black student-athletes aren't 100 percent. A 2018 report shows that just 55 percent of black male college athletes from Power Five schools graduate within six years. That's far less than the 69.3 percent graduation rate among all NCAA student-athletes.

And NCAA football and basketball is already like the NFL or NBA. Nothing about the ridiculous coaching contracts, larger-than-life stadiums or valuable TV deals says amateur. The only ones not getting a piece of the pie are the student-athletes like Zion Williamson turning March Madness into a cash cow.

What is the Fair Pay to Play Act?

GRAND SLAM!!

We hit it out of the park!We're about to end the exploitation of California college athletes.

The CA Assembly just passed #SB206, the Fair Pay to Play Act, with ALL yes votes!! https://t.co/cXocwhPTFX

— Nancy Skinner (@NancySkinnerCA) September 10, 2019

Drafted by California senators Nancy Skinner and Steven Bradford, the Fair Pay to Play Act (Senate Bill 206) essentially tells California colleges they have to allow student-athletes to sign contracts, hire agents and be paid for the use of their names, images and likenesses. They would still be unpaid students. As Sports Illustrated lays it out, these universities would then be forced to choose between breaking NCAA policy or breaking state law.

The NCAA, of course, is not cool with this. NCAA president Mark Emmert wrote a letter to the California senate saying if the the act became law that California colleges and universities would be ineligible to play in national championships. That's because the best athletes around the United States would presumably prefer playing for a major school in California where they could make money, which would make for an unfair competitive advantage for schools like Stanford, UCLA, USC and California.

The fallout in college athletics from this could be enormous. If the California bill is passed, the Pac-12 could expunge its California schools from the league. But they would likely begin their own league and have little problem keeping fans. Other states could follow suit (some, like South Carolina, are already considering it) if that were successful, which is exactly what the NCAA doesn't want.

The California State Senate voted 73-0 in favor of the anti-amateurism act on Sept. 9 and is still working on the act's language. After that, Gov. Gavin Newsom will have 30 days to sign a final version of the bill that wouldn't go into effect until 2023. It could still (and likely will) face challenges from the NCAA and federal legislation.

Apparently one challenger is Tebow, and his take entirely missed the mark.

It's OK to be privileged. We should all want the opportunities Tebow's been given in life. Like Tebow, I've been afforded the same circumstances. But he has to acknowledge them and consider not everyone's reality is the same as his.

Please, let these kids make a few bucks.

UPDATE: On September 30, 2019, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the Fair Pay to Play act, making it a law in the state. If the law survives expected court challenges, college athletes in California will be able to profit from their likeness beginning on January 1, 2023.

The NCAA hasn't said whether or not the law will definitively impact national status of the state's college athletic programs.

This article was originally published September 19, 2019. It's been updated with information after the Fair Pay to Play Act was signed into law later that month.